Combining my two great loves, history and art, I want to look at some of the imagery used to depict Plantagenet kings during the period and taking a few examples examine what the visual language may be telling us about how kingship was viewed and how the kings themselves wanted to be perceived.

Imagery as propaganda – of course, imagery linked to concepts of status and power – certainly, imagery as a means of establishing a link with another age – well that’s much more subjective yet many of us might admit to studying the faces of those kings whether it be on their tomb effigies or in portraits which have survived and longing to understand them or to read something of their drives and motivations from the shading and stance, the lines on their faces and the expression of their gaze. This is a very understandable human response to the mystery of their real personalities and the desire to understand the psychological influences which formed them as human beings.

How much of our relationship with these kings is influenced by visual representations which have survived even at a sub-conscious level? Has our relationship with image changed so much over time?

We are told that the medieval period was highly ‘visual’, many could not read or write and therefore the language of imagery held a special significance and power whether that be in terms of religious experience, daily life, in warfare or in death.

People drew comfort and solace from meditating on images of saints and holy figures in stained glass, painted wall art, statuary or textiles or in pouring over the images of illuminated manuscripts and books of hours among the elite class and understood and experienced the imagery of religious art at both a collectively spiritual and deeply personal level.

Medieval king in stained glass, York Minster

Pagentry and ‘show’ were essential as demonstrations of status and power and even routine events like serving dinner became ritualized visual spectacles with symbolic meaning. Power and patronage were inextricably bound up with the visual, from salt cellars and coats of arms to particular colours chosen to adorn the room or the persons of the guests. Elaborate food presentation, elaborate visual courtesies and allegory were woven into the fabric of life.

Richard II dining with the dukes of York, Gloucester and Ireland

On the field of battle too there were visual signs to be read and absorbed everywhere. Recognizing heraldry and being awed by the visual display of armour and weaponry were essential to the whole procedure of war and visual symbols became imbued with multiple layers of meaning and significance for those taking part. Personal badges, like mottos, were chosen for their significance and yet their meaning was also ambiguous and personal to their owners. Servants wore the livery badge of their lord or king and affiliations grew up around these powerful figures who were identified by these symbols as well as by their names and heraldic coats of arms.

Edward III and the Black Prince, wearing crowns and the royal arms including the lillies of France, depicted as warrior princes

Kings were represented in many forms – on seals, coinage, in manuscripts, as sculpture, on altarpieces, in books of hours, in tapestries and formal portraits and occasionally as caricatures. They were sometimes so symbolic as to be interchangeable; images of kingship which transcended the particular person holding the office and at other times intensely personal, as on their tomb effigies, yet almost always recognizable by the trappings of royalty, whether that be the crown, orb and sceptre, kingly armour or robes of state which they wore.

Doom painting depicting a mixture of social orders including kings and bishop being dragged down to Hell

Visual language remains a complex area of human experience, open to many interpretations. There is a mystical element in deciphering exactly what was intended by the creator or how it may be interpreted by the viewer and given the passage of hundreds of years of changing perceptions it is debatable how closely we can ever look with the eyes of those who first saw and absorbed these visual images. For all our knowledge of allegory and allusion, our understanding of christian teaching and ability to relate specific spiritual references to individual kings, it is this mystery at the heart of imagery which makes it so tantalizing and fascinating to study. We must ‘feel’ our way towards understanding intuitively and acknowledge the subjectivity of our approach.

We are also a very ‘visual’ age, we absorb multiple images at breakneck speed, zigzagging between emotional responses and conflicting mental processes often with alarming and unsettling consequences for our personal well-being. Few of us today have the luxury of meditating upon one image as we imagine they did or noticing the subtle visual language of the world as we try to process the mass of visual information around us, cluttered with commercial advertising and political propaganda and viewed through multiple media formats yet we still produce artists who work in intricate detail and poets who stop to look at the ivy on the wall and distill their experience into a few apt words.

In our efforts to bridge the great divide between their world and ours, perhaps we are able to catch brief glimpses which illuminate our understanding and also allow us to question preconceptions about how medieval people saw and processed what they saw and what that tells us about the iconography of medieval kingship.

Medieval Kingship as ‘symbol’:

This is Edward I’s great seal. He stands on royal lions or leopards and holds an orb and sceptre whilst being seated on his throne as symbol of his authority and judgement.

This is Edward III’s great seal. The king is shown in armour with a drawn sword which symbolizes both justice and the rightful defense of his realm.

The format of these great seals remained unchanged throughout the period. The seal was two sided, representing the two core responsibilities of kingship; namely to dispense justice and uphold the law; represented by the seated king on his throne with the orb and sceptre and to defend their kingdom on the field of battle; shown as a warrior leader on horseback with sword and shield and great helm. The wording running around the edge of the seal holds the key to which particular king is being represented but other than stylistic variations which might allow the viewer to date the image, the kings could be interchangeable. This is symbolic kingship through visual imagery representing continuity and permanence, divinely appointed authority and a pact made between the ruler and his people. Seals were a visual and legal affirmation of the king’s will and consent but always represented through images of authority and leadership.

Illuminated manuscript showing King Stephen, Henry II, Richard I and King John as patrons

In this manuscript image we have four kings holding models of building projects that they were associated with. There is no attempt to depict each king distinctly, they are again symbolic representations of kingship in an idealized format. Just as with the seals these are kings enthroned and crowned, pious and ordered, responsible for constructing beautiful buildings to the glory of God and symbols of permanence and durability, stability and civilization. They are patrons and benefactors as good kings should be. They are models as much as the buildings they are holding of values and relationships which transcended a particular individual although each king favoured his own projects and developed a personal connection with specific locations and monastic orders.

Of course in an age before photography many of the artists who depicted a particular king may never have seen him in the flesh or even been alive at the same time as some of the rulers they were painting so a certain amount of ‘artistic licence’ must be accounted for in how they chose to portray a specific individual monarch. They might attempt to show a particular fashion – many portraits of Richard II show him with a forked beard including his tomb effigy – yet the facial features are so indistinct as to be interchangeable with any other figure in the same manuscript. Illuminators each had a ‘house style’ which becomes instantly recognizable to the trained eye – a Froissart illustration, for example, or a scene from the Luttrel Psalter is instantly identified by the style of the illustrations in the margins as well as the colour palette used. We know who is being depicted by the context, the clothes they wear, the setting in which they appear etc rather than by any attempt at realistic ‘portraiture.’

Similarly in coinage it would be hard to name the specific monarch without the presence of lettering or some other means of identifying the individual. Plantagenet kings remain wearing the same open crown and curly haired ‘bob’ for hundreds of years on groats and pennies.

Edward I groat

Henry VI groat

Heraldry is another way in which we are able to identify particular kings as they are associated with particular heraldic coats of arms or badges. One example is the image of King Richard II on the Wilton Diptych. He is shown as a young king around the time of his coronation, surrounded by saints who are associated with him because they held a particular significance for him personally and in the case of St Edward the Confessor because he was also a King of England. Richard kneels in adoration before the Virgin Mary and Christ child who are surrounded by angels. Each angel wears Richard’s personal badge of the white hart as does the king himself at the neck of his ornate gown. The imagery seems to suggest that there is a harmony between Heaven and Earth, between the king and his heavenly intercessors. As the format of a diptych proscribes, there is a balance between the two panels, between kingship and divinity, between those who have lived on Earth and those who dwell in heaven. Richard’s livery badge is symbolic on several levels, as a personal emblem but also as an indicator of affiliation. The angels are affiliated with the king as they bow around the Holy Virgin and Child and present Richard to her thus demonstrating his divine favour. The saints line up behind him too as an expression of his piety and their support and St Edward holds up the royal ring, the symbol of the union between the king and his people under God. The flag of St George is a further visual symbol which implies that heaven favours England in particular as well as specifically Richard as king. The golden background on both panels suggests that all those present are removed from the temporal world and elevated into the heavenly world of golden light.

Richard II and the Wilton Diptych

If we compare this image with Richard II’s tomb effigy there are some interesting points. This double effigy was commissioned during his lifetime around 1395 to represent himself and his first queen, Anne of Bohemia, and was to be modeled on the ‘corps’ or body of the king, so therefore presumably as close to lifelike as possible in representing the mature king shortly before his death. Richard wears no crown which might strike us a little surprising for a king who seemed at great pains to demonstrate his royalty whenever he was portrayed. The link below discussed the other famous portrait of him which is kept at Westminster Abbey and depicts him crowned and enthroned with orb and sceptre and notes the story that he would sit ‘ostentatiously’ on his throne in full majesty and command anyone who his eye fell upon to kneel before him. Edward III’s effigy also shows the king bareheaded so perhaps Richard was influenced in his decision by that striking and strangely ‘mystical’ representation of his grandfather which gives Edward III the feeling of a wizard as much as a king. Richard’s usurper, Henry IV, certainly made sure he was wearing a crown for all eternity on his effigy tomb at Canterbury.

Majesty with humility. Both images indicate his status by the rich robes he wears and the crown on the kneeling Richard but both are also pious before the greater authority of the divine. Whether Richard is physically kneeling or staring up at a canopy where there are symbols of divinity, it is essential that the image of the king is presented as both majestic and yet suitably awed before the Kingdom of Heaven.

Richard came to the throne as a child and therefore it is not unsurprising that the Wilton image has a very boyish flavour. He looks delicate and almost feminine with long fingers and rosy cheeks and appears smaller than the supporting saints behind him. In contrast the tomb effigy should represent him as a grown man yet there is still a lack of virility in the image despite the wider face and forked beard. How much of our ‘reading’ of the image in overlaid with our knowledge of his kingship and fate and how would contemporaries have viewed this effigy both before and after his deposition and death?

http://www.history.ac.uk/richardII/portraits.html

effigy tomb of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia in the Shrine of St Edward the Confessor, Westminster Abbey

Plantagenet kings chose to be clothed in robes of state in death rather than in armour despite the martial achievements of many of them. Edward I has no effigy, just a slab top tomb inscribed with – “Edwardus Primus Scotorum Malleus. Pactum Serva” (Edward the First, Hammer of the Scots. Keep Troth) but Edward III and Henry Vth both have effigies without armour. Probably the closest armoured effigy tomb to the actual throne is of ‘The Black Prince’ again in Canterbury with his achievements hung over his tomb. In contrast with the royal tombs at Westminster he looks both impressively martial and uncomfortable lying stiffly in full harness with his finger tips touching beneath his studded gauntlets.

The Black Prince at Canterbury

The royal effigies are remarkable for their lifelike quality and in the details of the gently flowing drapery of their figures. Great kings were above the knightly class who gloried in intricately detailed renditions of their costly harness as a means of demonstrating their status and military accomplishments in life. Kings were closer to the saints and to God and perhaps wanted to rest for eternity in greater style and comfort in their coronations robes like Edward III. The significance of the coronation as the defining moment of their lives can not be underestimated nor the compulsion to refer back to it again and again in the iconography of kingship. The throne, the orb and sceptres as well as the crown and robes appear over and over again in the images which we associate with these kings as a means of defining them and giving credibility to their authority.

Edward III in his coronation robes. His effigy may have been modeled on the wooden funeral effigy taken from a death mask

Edward III’s effigy is fascinating because it shows the king in age with a lined face. We still have the wooden funeral effigy which was made to top his coffin on it’s last journey to Westminster and was modeled on his death mask. The drooping line of his mouth suggest that he may have suffered from a stroke (probably a series of strokes according to accounts of his last days). The modelling of the brow line and eyes certainly seems to follow the form of the wooden effigy and therefore may again be pretty realistic even though the treatment of his hair is stylized as with the other royal tomb effigies.

This link gives more detail on Edward III’s tomb effigy at Westminster

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/royals/edward-iii

The design of royal tombs within the shrine of St Edward the Confessor conform to a similar style of presentation even allowing for individual representations in order to give a sense of harmony in the space and also again a feeling of unity and continuity among Plantagenet kings. To be included in this most holy and significant of places was a fitting honour for those who shared a bloodline and the burdens of kingship so it was fitting that their tombs should echo one another even within the conventions of their age.

Portraiture is the most obvious source of royal imagery and yet beset with problems when it comes to reaching out to the person of the king. The Golden Age of court portraiture was yet to come. The breathable portraits of Hans Holbein would have been a wonderful resource for us if he had been able to sketch the Plantagenets but sadly those portraits that survive are usually later copies of originals that are now lost to history and often frustrate as much as they tantalize us. They seems irritatingly two-dimensional and unsatisfying compared with tomb effigies. More like pub signs than windows into the king’s soul. Here are a few examples:

Henry IV

Henry Vth

Henry VIth

These three Lancastrian rulers wear chains of office, one holds a sceptre, much is made of fine hands and rings, only Henry IV makes eye contact with the viewer which feels like a challenge. Henry Vth may have been painted in profile to disguise the jagged scar beside his nose which he received at the Battle of Shrewsbury. Many read into this portrait the outward signs of his determination of character in the lantern jaw and passionately thickset lips. Henry VIth seems gentle and passive but how much of that is due to overlaid reading based on our knowledge of his character and ultimate fate and how much due to the wide-eyed vacancy of the image and parted lips? If we knew nothing about him would we view the image differently? Would we even know he was a king by the clothes and jewellery that he is wearing?

Later portrait artists created whole sets of royal images, usually based on a few lost originals to decorate the panelling of stately homes and the houses of the ‘noveau riches’ families who sprang up during the Elizabethan and Stuart monarchs. Many of these images now pop up when you search online or appear on the cover of historical biographies as if they represent the true character of the kings they seek to portray yet most are, at best, a poor copy of a copy of an original and how close were those original portraits to the reality of the person they portrayed? Kings liked to be flattered and portraits were often commissioned for a specific purpose – to be seen by a specific audience for a specific reason such as during marriage negotiations when the king might be forgiven for wanting to look his best! Are they any less formal or ‘symbolic’ in nature than other images of kings or seals or coinage?

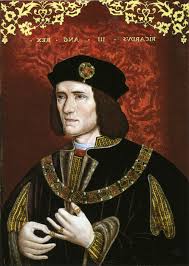

I think it is fairly safe to assume that later artists altered some of the images of medieval kings as well. The most obvious example of this with heavy overtones of political propaganda is the portraiture of Richard III which we know was altered significantly after his death by Tudor painters in order to give him a noticeable hunchback and sometimes the suggestion of a withered or distorted arm. X-ray photography allows us to see where the line of his shoulder has been heightened and his fingers made to look distorted but also there are more subtle details like the lines around the mouth and thinning of his lips to make him look both older and more stern.

Richard III with distorted shoulder which was over-painted after the original portrait was completed

This painting which is housed in the National Portrait Gallery has been tree-ring dated to the late C16th but may be based on an original which is now lost. Like the painting of Richard shown below the collar of his robe has the same pattern of circular rings though his cap badge is not the same yet the visual impression is completely different. It is, of course, possible that one was painted before he became king and the other later when grief and the burdens of kingship had taken their toll but as he died at the age of 32 it would appear that someone was at pains to age him in these later Tudor portraits.

Portrait which shows a more youthful and open expression on his face

This link to the Richard III Society page goes into more detail about the way in which portraits of the king were later distorted for political purposes.

http://www.richardiii.net/2_4_0_riii_appearance.php

This recently restored portrait may be closer to the reality of Richard as he was at the end of his life. He appears slight and there is a suggestion of irregularity in the shoulder line but he looks young though pale and drawn. It is thought that this portrait may have been specifically commissioned by Richard after the death of his queen, Anne Neville, as part of negotiations for a Portuguese marriage alliance.

Recently restored portrait of Richard III which may have been commissioned as a negotiation aid for a potential marriage alliance with Portugal

The recent discovery of his skeletal remains and reconstruction based on his skull gives us the rare opportunity to compare a 70% accurate representation with contemporary portraiture and there are some striking similarities.

Looking at Richard’s skull we can see that the National Gallery portrait does prove a good match with his jawline and eye setting. The reconstructed head also matches these features though the nose had to be constructed based on approximate measurements as soft tissue is lost over time. Like the death mask of Edward III it is close enough to be recognizably the likeness of the person even given variables of eye and hair colour.

Enter a caption

So perhaps some of the likenesses we have are close enough to the reality of the kings they represent for us to pick them out in a room yet still tantalizingly opaque when it comes to inference. Do we see what we want to see and wasn’t that always the case? By the end of the Plantagenet period the ideology of the Renaissance was having an impact on the way in which portraits were painted. Not only was there greater emphasis on realism in skin texture, cloth and form and perspective but also the ideals of humanism were changing the way in which portraits were being painted. Perhaps we can allow a tiny element of this desire for ‘artistic truth’ to colour our response to how Tudor painters thought Richard III should be depicted based on what they believed to be the real nature of his physical appearance in the same way that Henry Tudor was portrayed with a squint in his eye even by his court artist. The king as an ‘icon’ was starting to give way to the king as both a man and a majestic presence. These kings wear soft caps and chains of office but their kingship is not immediately obvious. They look pensive and care worn and perhaps less invincible than the images of their predecessors but are even more fascinating for the complexity of their imagery.

Of course these kings would probably have been horrified at any suggestion of implied ‘weakness’ or transparency in their portraiture. A king needed to assume a public ‘mask’ in order to impress and awe his subjects. We are told by a court ambassador how Henry VII created an aura of majesty about him by his stillness and composure combined with wearing very expensive jewels and rich robes. Whatever he may have lacked in personal charisma he was at pains to compensate for by assuming a regal countenance and bearing.

In the Tudor period we see how reality and symbolism took on a new level of definition in the portraits of Henry VIII. The tyrant is clearly in the room but it is dressed in such magnificence that no-one would dare to look directly at it for fear of being blinded. Henry may not always wear a crown but his bestrides the canvas like a God. When you analyse his facial features we can see that the painters were true, he is fat and his mouth is pinched. His face is puffy and unhealthy and his eyes increasingly narrowed but he is presented in such a package of splendour and opulent display that the man is lost in the illusion of power.

So then, images of medieval kingship across a range of media, all deeply influenced by the nature of power and the relationship between the office of monarch and the visual imagery of their times. Kings as icons and symbols, kings as mediators between the unknowable realm of heaven and Earthly mortality, kings as patrons and benefactors, as law givers and warrior leaders, kings as symbols of continuity and permanence and sometimes just glimpses of the real men beneath the majestic facade.

We can never know what their images meant to their contemporaries, how much their subjects revered or despised their iconography, how much people thought about their kings as real people rather than as leaders or semi-divine presences on Earth. The fascination remains though with every depiction of our Plantagenet kings, the niggling desire to look at the devil in the detail and try to make connections with men who we have read so much about and yet who still remain such enigmas.

December 4, 2015 at 11:59 am |

Reblogged this on murreyandblue.

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 9:31 am |

I do wonder if the image of Henry VI is actually comtemporary. If not it raised the possibility of some alteration by Yorkists methinks. They were very good at dragging thier rivals names through the mud and rewriting history in their own favour, so why not change paintings?

Would the Richard III soceity let that be spread abroad? One does wonder…..

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 10:43 am |

It is quite possible that Henry VI has been portrayed in a particular way for propaganda purposes both in portraiture and in contemporary source material. I am open to this possibility. Both sides used propaganda and smear tactics during the Wars of the Roses including Richard III himself. The Titulus Regius certainly reads that way. I don’t think ‘Ricardians’ can all be tarred with one brush anymore than all Lancastrian sympathisers can either. Nuance is possible and an attempt to be fair and balanced. I have always felt much sympathy for Henry VI on a personal level and I’m sure it was a hard time to be alive for anyone suffering from a mental condition due to contemporary views, just as it must have been to have Scoliosis!

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 2:20 pm

There is an interesting argument that the notion that everything began with the events of 1399 was actually something that originated with the Yorkists, and that Shakespeare’s depiction of some key figures of the WOTR such as Margaret of Anjou and Suffolk was essentially based on Yorkist propaghanda.

I do find many people who say the opposite have not actually read or seen many of his Plantagenet Plays, or the Henry VI trilogy…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 23, 2016 at 2:41 pm

Sorry if I caused any offence. I don’t want to tar all Richardians- I suppose bad experience of encountering people who represent the extremes of that postion has caused me to throw out the baby with the proverbial bathwater.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 23, 2016 at 2:36 pm |

I agree, particularly with regard to Marguerite of Anjou. I have always maintained that Marguerite was in a difficult and dangerous position and her actions have frequently been viewed from a negative and male perspective without taking into account the constraints which applied to her ‘power’ and her desire to protect the interests of her husband and son. I enjoyed reading Helen Castor’s book on ‘She Wolves’ very much and certainly think she is due a major reassessment. I dislike knee jerk reactions to real historical figures to fit a fixed agenda.

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 2:54 pm |

I can only reply down here I am afraid. One thing that I find frustratingly odd about Margeret is that people seem more willing think ill of Margaret, and believe and accept the rumours and insinuation about her than any other Queen of England.

There is really no evidence that her son was fathered by anyone other than Henry VI for instance, or that she was an adulteress. In fact, I was reading about some of the correspondance between her and her husband, and I wonder if there was genuine affection between them……

As for her controversial actions- well I really do not believe she was any more violent or ruthless than the men around her- nor politically grasping. Her background would suggest she was quite used to the idea of women running things in the absence of a man- and of course in France there was a precedent for female Regency. I really ought to read that book on her Grandmother Yolande of Aragon and Joan of Arc I have on my shelf….

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 23, 2016 at 5:14 pm |

I agree with you. I think half the sources were poisoned against her just becaue of the terms of her marriage contract and always suspected that she still had a foot in the French camp throughout her marriage. It was a difficult juggling act for any of the young women who were sent across Europe to be brides and diplomats and intercessors. they were always trying to please their family and their husband who usually had very different agendas and trying to make a life for themselves and protect their children too. I certainly don’t envy Marguerite at all and the point about her being ‘worse’ than her male counterparts is invalid. The Lancastrian army hada poor track record at times but how much of that can be directly blamed on Marguerite is very questionable.

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 7:10 pm |

From what I read, especially in 1460, I wonder if Margaret’s ‘Lancastrian’ army really was so bad. It seems to have been more a case of stirring up fear of the evil ‘Northerners’ or heaven forbid- Scots! I am sure forces mustered by the Yorkists also were not adverse to ‘foraging’ as it was known- stealing food etc.

(I put the words in inverted commas as I do not things were always as ‘black and white’. For instance, Warwick’s sister was married to Richard de Vere, Earl of Oxford…)

I don’t know what to think of Richard. I don’t like Edward IV, or his father much- I think they were power-crazed and killed everyone who got in thier way, including siblings and relatives- and frankly Edward’s freindship with Tiptoft ‘the Butcher’ and his activities cannot be justified in terms of pure survival I think.

I don’t like how Richard helped himself to the lands of widows, like Lady Hungerford, by less than honest means- but when it came to grabbing power by force and eliminating any who got in the way well- he’d seen his family doing it, so should be be be surprised if he followed suit?

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 7:54 pm

How exactly was Richard, Duke of York power-crazy and who did he kill that “got in his way”? For someone so “power-crazy”, it sure took him a long time and increasingly limited circumstances to assert his claim to the throne. For that matter, how exactly was Edward IV power-crazy? By which standards? Compared to who? Why did Edward make peace with so many Lancastrians, including the Somersets in the first decade of his reign, if he was “killing everyone who got in his way”?

I find it really ironic that you’re complaining about Yorkist propaganda, and then you start saying things that sound like really extreme Lancastrian propaganda.

LikeLike

January 24, 2016 at 8:25 am

Time Travelling Bunny- have you read about the first Battle of St Albans in which the only major noble casulties just so happened to be the main political rivals of himself and his freinds? Ever read about the executions after pretty much every major battle which finished off all the male Beauforts as well as the de Courtenays etc….?

Ever read about his Edward’s ascension to the throne was followed by the single bloodiest battle ever foung in English history (Towton), or how Edward allowed his friend Tiptoft ‘the butcher of England’ to put into practice new and horrible methods of execution on those convicted of ‘treason’? Ever read about how the same man, when Edward sent him to Ireland, caused a rebellion in that country by Killing the Earl of Desmond, then hanging his children and had to be called back?

Ever read about the complaints that were made against Edward in 1469? No? Sorry, but I have read about this period quite extensively, and learned about it under one of the country’s foremost experts on fifteenth century English History- and have forumlated my opinions from that.

The Yorkists eliminations of all who opposed them or got in thier way- including thier own siblings, cousins, former King etc, are well documented historical facts. They did anything they deemed necessary to get hold of and to keep hold of power.

You cannot just call everything you disagree with, or any fact you do not want to accept ‘Lancastrian propaghanda’- well you can, but its tantamount to burying your head in the proverbial sand.

The Yorkists were not perfect- they were ruthless and bloodthirsty. They were not innocents, nor were they holy and righteous. To pretend they were any such thng is a gross distortion of history……

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 5:21 pm |

The ‘Ricardian’ point is an interesting one and both sides are guilty when it comes to tarring things! It is a very contentious area and sometimes it is hard to get over the nuances in the argument when people from the ‘other camp’ are reading blogs, posts etc… I take as open an viewpoint as I can on Richard. I find much to admire and some things to sympathise with but I totally accept that he was a product of his age and capable of actions that we would now regard as morally questionable including possible involvement in the death of Henry VI. He was caught up in a dangerous game and no more saintly or evil than anyone else and the same can be said for all the major players. They made mistakes and acted for self interest and they tried to survive in hard times. I try to see them all as human beings in need of understanding as much as judgement.

LikeLike

January 23, 2016 at 7:16 pm |

I think one thing that gets on my nerves is the hypocrisy. How some Richardians seem to vilify other historical figures in the way they have protested the vilification of Richard III.

Just because Henry Tudor defeated Richard does not mean he was Satan incarnate- a number of historians I have spoken to have actuall assessed him to have not been a bad King on balance. I think it was to do with his financial and adminstrative policies, and patronage of the arts.

That said even Henry VI established Eton and King’s, one almost wonders if things had been diferent would he be seen as a prototype Renaissance Prince more interested in learning than war?

LikeLike

January 24, 2016 at 10:58 am |

It is sometimes said that Elizabeth I was the first monarch to make a conscious attempt to project ‘image’. I think it was Richard II. Sadly for him, he was much ahead of his time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

February 25, 2016 at 11:31 am |

I think it goes back much farther than that. Alfred the Great commissioned a biography of his deeds to be written down so that his fame could be remembered down through the ages and his grandson Athelstan projected himself as an English Charlemagne including the imagery of his coinage and in contemporary manuscripts. Kings were always interested in how they were portrayed because visual images have such power.

LikeLike

September 22, 2017 at 12:59 am |

each time i used to read smaller articles which as

well clear their motive, and that is also happening with this paragraph which

I am reading at this time.

LikeLike

September 22, 2017 at 7:58 am |

Hi, Not sure I understand what you’ve posted here. Could you clarify for me please?

LikeLike

December 23, 2020 at 4:27 am |

Visit: http://Plans7.com

LikeLike